The Person of the Theotokos in Protestant Theology*

By Presbyter Basileios A. Georgopoulos, Th.D.

If one wished to set forth the way in which Protestant theology—at each stage in the evolution of Protestantism—approaches the Theotokos, this would undoubtedly exceed the scope of an article and would necessitate the writing of a voluminous work.

However, the goal of our brief historical and dogmatic consideration is simply to detail the deviation of Protestant theology from the confession of the Church on this subject, as the bearers of Divine Revelation witness to it, and at the same time to note the incredible erosion of Protestantism by way of rationalism and intellectual arrogance.

Starting with the leaders of the Reformation, we might remark that Luther held a pious position before the mind of the Church, with regard to the attributes of Mary, calling her the Birthgiver [Mother] of God and Ever-Virgin. Never did he question these two attributes, [1] and he similarly presented her as the prototype of humility and faith.

Fearing to minimize, nonetheless, the uniqueness of the mediation and work of Christ, he submitted to criticism, in various ways, statements of honor to the Theotokos, just as he also rejected the supplication of her intercessions. [2] Operating within these same boundaries were Zwingli and Calvin, who confessed the attributes of the Mother of God as Theotokos and Ever-Virgin, while rejecting the supplication of the intercessions of the Theotokos. Calvin was, indeed, the most combative and obdurate of polemicists in resisting any form of honor to Her. Any sort of honor towards the Theotokos he reckoned idolatry. [3]

We should underscore that, concerning the negative position of the Protestant leaders with respect to honoring and the supplicating the intercessions of the Theotokos, the errors and hyperbole of medieval Papist Mariology, among other things, definitely played a role in this issue. A typical example of this is the case of Frederick the Wise, the Elector of Saxony, who, in a list he made in 1520 of some 19,013 “sacred” objects, included four strands of hair from the Theotokos, as well as a whisp of hay from the Cave of the Nativity in Bethlehem. [4]

In the Confessional Statements of Protestantism, both of the Lutheran stripe (e.g., the Augsburg Confession, article 3, and the Schmalkald Articles, articles 1 and 4) and that of Calvin (e.g., the Heidelberg Catechism, article 35 [to be precise, this article refers to Christ as having taken upon Himself the “very nature of man” from the “flesh and blood” of the Virgin Mary]), as well as the Formula Concordiae of 1571 [sic; 1577—Trans.] (summary articles 8 [sic; article 7—Trans.] and 12), upheld the belief [either—Trans.] that the Mother of God was truly the Birthgiver of God... [or—Trans.]...Ever-Virgin. [5] At the same time, they rejected any form of honor for, supplication to, or intercession by Her. [6]

Socinus, the anti-Trinitarian heretic, constitutes an exception in this epoch, as he denied Her attributes as Theotokos and Ever-Virgin. [7] This kind of confession in Protestantism concerning the Theotokos, as it was expressed in Reformation confessional documents, was to endure until the end of the seventeenth century, representing—from the standpoint of the development of Protestant thought—the so-called classical Protestant Orthodox position on the matter.

The reason that there was no doubt, during this period, about Mary as the Ever-Virgin Mother of God is that the Christology of classical Protestant Orthodoxy followed to a great degree the Christology of the Undivided Church. [8] Contrarily, however, from the eighteenth century on, in the age of Neo-Protestantism and the dominant currents of the Enlightenment, Pietism, and Subjectivism, classical Protestant Christology came into doubt and the person of the Theotokos was diminished in honor.

For Schleiermacher (11834), because of his Neo-Sabellian Triadology and his heretical Christology, these two attributes of the Theotokos had no place whatever in his theology. [9] This impugnment of the Mother of God underwent further development in the so-called Protestant Culture movement of the nineteenth century, right up to the beginning of the twentieth century. Rationalist criticism and the liberal Protestant theologians (D. Strauss, Chr. Bauer [sic; i.e., F.C. Baur— Trans.], A. von Harnack, and others) called into question every element of the miraculous, ignored ancient ecclesiastical tradition, and, showing contempt for older Protestant teaching, came to speak of “myths” with respect to the person and attributes of the Theotokos.

Already in 1836, D. Strauss, in his celebrated work The Life of Christ, had characterized the supernatural conception of the God-Man as a myth which crept into the Biblical narrative from Greek mythology. This already contemptuous and demeaning approach to the person of the Theotokos was sustained by twentieth-century Protestantism in the school of religious history (religionsgeschichtliche Schule).

Representatives of the religious history school (M. Dibelius, W. Bousset, E. Norden, et al.) came to equate the Theotokos with the goddesses of other religions. [10] Similarly, they attempted to prove that the relevant Biblical narratives of Matthew and Luke, in reference to the Theotokos and the birth of the God-Man, were derived from the mythologies of Egypt and the Near East. [11]

By contrast, the principal expositor of Dialectical Theology, K. Barth, [12] maintained respect for the attributes of the Ever-Virgin Theotokos, while E. Brunner [13] denied that the Theotokos was Ever-Virgin. Nowhere did the person of the Theotokos suffer worse treatment than in the attempt to “demythologize” Holy Scripture by R. Bultmann and his associates. For another famous Protestant theologian, W. Pannenberg, [14] the Eternal Virginity of the Theotokos was also a myth.

In the twentieth century, Protestant theology has likewise revived the arguments of ancient Jewish anti-Christian polemics against the Eternal Virginity of the Theotokos. [15] Among such arguments, for example, is the claim that the passage from Isaiah 7:14 [affirming the conception of Emmanuel by a Virgin—Trans.] employs in Hebrew the word “Almah” (a young woman or maiden) and not “Bethula” (virgin), which was supposedly translated incorrectly by the Seventy [i.e., in the Septuaginta—Trans.].

Also, there will always remain the classical Protestant support for that monument of rationalism, the claim that the confession of the Church regarding the Theotokos as the Birthgiver of God and Ever-Virgin is a remnant of a pre-scientific understanding of the world and of events. [16]

The views of [most of—Trans.] contemporary Protestantism regarding the Theotokos are sadly disdainful and scornful. This is reinforced by the evolution of Protestant Christology, which, except in very few instances—both over time and in our day—has taken on, in some cases, a Neo-Arian character and, in other instances, a Neo-Nestorian quality.

For the Orthodox Christian, these Protestant perceptions are statements not only about the continuing, indescribable tragedy of Protestantism, but simultaneously have a heretical and blasphemous quality about them. Indeed, as St. John Damascus says: “Away with this! One of chaste mind considers not such thoughts.” [17]

Endnotes

1. Weimarer Ausgabe, II, pp. 434-435 [A 120-volume collection of Luther’s works, in German, entitled D. Martin Luthers Werke—Trans].

2. Ibid., II, pp. 312, 348.

3. Stimm, M.L. (1892), p. 460 [in German]. See Presbyter B. Georgopoulos, “A Critique of J. Calvin on the Holy Icons,” Athens, 2000, pp. 8-10 [in Greek].

4. Bainton, Poland [sic; Roland], Here I Stand: [A life of—Trans.] Martin Luther trans. G. Zerbopoulos (Piraeus: 1986), p. 48 [in Greek].

5. Müller, G.L., “Principles of Catholic Mariology in the Light of Evangelical Questions.” Catholica, 35 (1991), pp. 181-192 [in German].

6. Grane, L., The Confessio Augustana (Göttingen, 1996), pp. 161-164. See J. Röhls, The Theology of Reformed Confessional Writings (Göttingen, 1987), p. 238 [in German].

7. von Harnack, A., The History of Dogma (Tübingen, 1991), 8th ed., p. 451 [in German].

8. Matsoukas, N., Protestantism (Thessaloniki: Ekd. P. Pournara, 1995), pp. 53-56 [in Greek]. See I. Karmires, Orthodoxy and Protestanism (Athens, 1937), Vol. I, pp. 269-270 [in Greek].

9. The Christian Faith (Berlin: 1830-1831), 2nd ed, Vol. I, 96.97:2; Vol. II, 172:3 [in German].

10. Prumm, K., The Christian Faith and the Ancient Pagan World (Leipzig: 1935), Vol. I, pp. 233-283 [in German].

11. Merkelbach, B.H., Mariologia (Paris: 1939), pp. 121-124 [in Latin].

12. Church Dogmatics (1932), 1.1, p. 510; 1.2, pp. 189-221 [in German].

13. Brunner, E., The Mediator as a Determinant of Christian Belief (Zurich: 1947), 4th ed., pp. 288-289 [in German]; idem, Man in Revolt (Berlin, 1937), pp. 10-12ff [in German].

14. Pannenberg, W., The Confession of Faith (Gütersloh: 1982), pp. 81- 83 [in German].

15. Justin Martyr, St., “Dialogue with Trypho,” 43, 8.367, 1.71, 1, in Library of Greek Fathers and Ecclesiastical Writers, Vol. III, pp. 246, 271-277. See Eusebius of Caesarea, “Selections from the Prophets,” 4.4, Patrologia Graeca XXII, cols. 120 1CD-I2O4ABC.

16. Künneth, W., Fundamentals of the Faith (Wuppertal: 1980), pp. 113-114.

17. John of Damascus, St., “Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith,” Book IV, chapter 14 [in Greek]. English text that of the translator.

* This article appeared in the periodical KotvwvIa (Koinonia), April-August, 2002, pp. 133-135. The author is a consultant to the Commission on Heresies of the Holy Synod of the State (New Calendar) Orthodox Church of Greece, which jurisdiction he serves as a clergyman. Translated from the Greek original by Archbishop Chrysostomos of Etna.

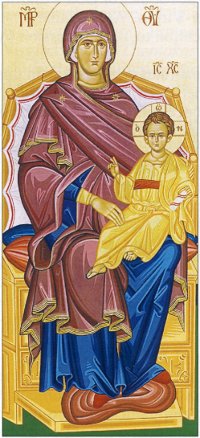

Note—The Icon of the Theotokos that appears on the first page of this article is from a panel painted at the Icon studio of the St. Gregory Palamas Monastery and found at our Exarchate parish of St. John Chrysostomos in Saugus, MA.

From Orthodox Tradition, Vol. XXVI, No. 2 (2009), pp. 11-14.